Back to Topics │ Bias as a concept │ CheatSheetHub │ Start: Relativity & Reaction

This cheat sheet provides the detail needed for Bias as a Concept & Climbing the Stairs.

Daniel Kahneman distinguished System 1 as “fast, automatic, intuitive” and System 2 as “slow, deliberate, logical” (Kahneman, 2011). These modes shape how we deal with everyday situations — often without realizing it.

Observation: Pattern Recognition

Pattern recognition is the process of identifying an observed object by comparing it against memory and iterating to the closest match.

My father was an amateur ornithologist, and I accompanied him when I was young. I learned with him how to identify birds where this recognition became very conscious. Often, I would wait until the bird exhibited a particular behavior to provide the key to its identity — for example, the hovering of a kestrel.

Observation: Functionality of Pattern Recognition

Pattern recognition is a fundamental capability present in virtually all animals. Implementation differs across groups — mammals, birds, reptiles, insects, and others — depending on sensory emphasis and neural structure.

In mammals and birds, pattern recognition is especially developed in vision — though in species such as dolphins, bats, and owls, hearing provides the dominant channel. In mammals, advanced pattern recognition is distributed across layered cortical circuits, whereas in birds it relies on clustered pallial structures that perform similar computations.

Senses other than sight are selected for advanced pattern recognition when sight does not yield sufficient information about the surroundings.

Pattern recognition is a good example of what could take place within a computer or within the human brain.

- The brain is a network of billions of neurons whose connections support recognition (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020).

- A computer requires a program to instruct its processor what to do and which databases to use.

In computers, recognition follows explicit coded rules. In the brain, recognition emerges from networks of neurons acting in parallel — but both serve the same function: mapping input against memory.

Preprocessing begins in the retina and continues in the thalamus (specifically the LGN). Robust object separation and identity emerge in cortical visual areas, especially the ventral stream (Livingstone & Hubel, 1988).

The cortex then delivers functionality analogous to the theoretical code — applying priors and updating beliefs (Knill & Pouget, 2004).

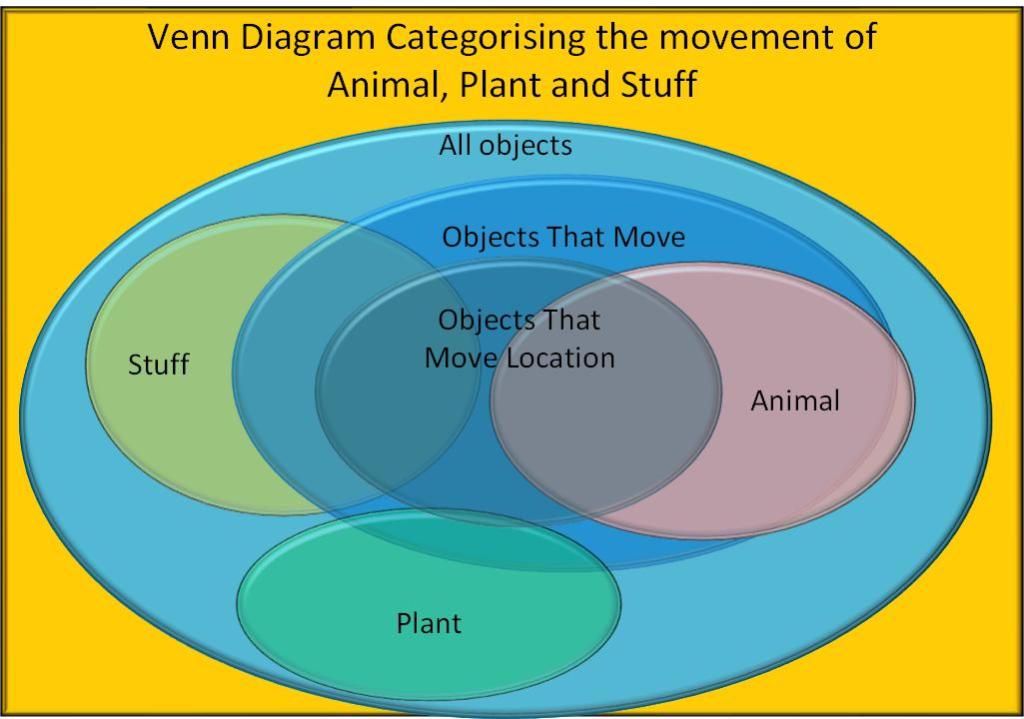

Motion Categories

An object has three real states of motion:

- Static – non-moving (i.e., a wall, tree with no wind, stonefish)

- Fixed location – motion without displacement (i.e., flag, wheat blowing, bird singing)

- Moving location – motion with displacement (i.e., car driving, leaves falling, elephant walking)

Objects that change location form a subset of all moving objects.

Sometimes the data provided about an object is insufficient to yield a definitive state of motion. In such cases, an Unknown marker is set — and this too can be useful in identification.

For simplicity, I’ll use old categories as teaching buckets (not strict science):

- Animal (i.e., stonefish, bird, elephant)

- Plant (i.e., tree, wheat, leaves)

- Stuff (i.e., wall, flag, car)

Classifying an observed object narrows the search space in memory. Using motion as a starting point skews the search toward more likely candidates and speeds recognition through the application of bias.

Theoretical Code Example

This code is not designed to run — it’s a simplified analogy to show how Bayesian inference can use bias to steer recognition efficiently.

// Simplified pseudo-code: not executable – models probabilistic recognition logic

// Legend

// ++ = strong positive bias

// + = moderate positive bias

// — = moderate negative bias

// —- = strong negative bias

// All probabilities normalized (sum = 1)

Define Object_as_Seen as Object_of_Interest

Function Template as Characteristics_of_Objects_from_Memory

If Template.Moving(Object_as_Seen) = “moving” then

If Template.MovingLocation(Object_as_Seen) = “moving_location” then

// Bias: ++ Animal, ++ Stuff, —- Plant

Else If Template.MovingLocation(Object_as_Seen) = “fixed_location” then

// Bias: + Animal, + Stuff, — Plant

Else

Set Template.MovingLocation(Object_as_Seen) = “Unknown“

// Logic: object ∈ moving set, subset unclear

// Bias: ++ Animal, ++ Stuff, —- Plant

End If

Else If Template.Moving(Object_as_Seen) = “Static” then

// Bias: —- Animal, ++ Stuff, ++ Plant

Else

Set Template.Moving(Object_as_Seen) = “Unknown“

// Logic: movement cannot classify

// Bias unchanged: Animal, Stuff, Plant

End If

// Bias Compensation Rules

If bias increase = +++ → apply —- compensation elsewhere

If bias increase = ++ → apply — compensation elsewhere

If bias increase = + → apply – compensation elsewhere

Observation: Where Pattern Recognition Fails

The diversity of pattern recognition across species reflects evolutionary branching — different lineages refining the same core skill through distinct anatomical solutions.

The evolutionary split between early mammals and the ancestors of modern birds occurred before the full expansion of advanced pattern recognition systems. Both lineages later evolved distinct yet functionally similar solutions.

This convergence suggests that advanced pattern recognition confers such a strong survival advantage that it evolved independently in multiple genetic lineages.

Since our focus is on how humans can apply these biological advantages in the modern world, we’ll now narrow the discussion to human cognition.

No recognition system is flawless — and the limits are easiest to see in optical illusions.

The illusion devised by Lionel and Roger Penrose in the 1958 and made famous by M. C. Escher’s Ascending and Descending (1960) is one of many that highlight the fallibility of human pattern recognition (Gregory, 1997).

Consequences: Pattern Recognition

An experienced ornithologist knows how to identify different species of bird. Sometimes this process must be slowed down and pursued strategically to observe a particular characteristic. That is System 2 — deliberate, logical analysis — sitting on top of the automatic System 1 mechanism.

Consequences: Functionality of Pattern Recognition

The program methods Template.Moving, and Template.MovingLocation, use information about the observed object. Their details could be complex, but their role is simple: determine which motion subset the object belongs to.

Equally important is setting Unknown markers, since these can guide later inference. In practice, such methods output likelihoods, not just Booleans, which can then be combined into posteriors — opening the door to Bayesian inference (Knill & Pouget, 2004).

The routine may yield an Unknown status when:

- the object is “moving” but cannot be distinguished as “fixed_location” or “moving_location,” or

- the object cannot be distinguished as either “moving” or “static.”

In both cases, Unknown is valuable information: it can be revisited later if the first search path fails.

Pattern recognition outcomes always depend on prior experience — the quality of the data collected in the past. As a learned skill, honed from birth and refined throughout life.

Consequences: Where Pattern Recognition Fails (Again)

Illusions elicit a consistent misinterpretation of the real world. Such perceptual biases are the Achilles Heel of System 1 thinking — and they hint at weaknesses in other System 1-based skills.

Bias is not confined to subcortical systems (brainstem, basal ganglia, limbic structures). System 1 also plays a significant role in the cortex, as shown by the fact that optical illusions trigger errors in cortical pattern recognition (Eagleman, 2001).

In a 2D image, parallel edges (e.g., road sides) appear to converge toward a vanishing point on the horizon. From the observer’s standpoint, the drawn road appears to narrow with distance. In reality, the lines have simply been drawn closer together — they are not further away.

Action: Based on the Consequences of Pattern Recognition

System 1 skills can be fooled, but there is a fix: we can deliberately switch to System 2, much like a pilot taking manual control from autopilot.

The takeout is:

- Keep training your abstract skills by consciously applying them.

- Recognize when slowing down and using deliberate thought pays off.

Reference List

These are the selected references used as a basis for the ChatGPT fact check

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Penrose, L. S., & Penrose, R. (1958). Impossible objects: A special type of visual illusion. British Journal of Psychology, 49(1), 31–33.

- Escher, M. C. (1960). Ascending and Descending [Lithograph].

- Bear, M. F., Connors, B. W., & Paradiso, M. A. (2020). Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain (5th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Gregory, R. L. (1997). Eye and Brain: The Psychology of Seeing (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Marr, D. (1982). Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. MIT Press. (classic on vision & pattern recognition).

- Gazzaniga, M. S. (2018). The Consciousness Instinct. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

📖 Series Roadmap

- Forward: A Little Background

- Introduction: Action, Reaction, and the Human Paradox (16.09.2025)

- Looking Back in Time: The Development of the Human Brain (23.09.2025)

- Abstract Senses: Enhancing the way we see the world outside (30.09.2025)

- Bias as a Concept & Climbing the Stairs: Pattern Recognition & Everyday Tasks (07.10.2025)

- Abstract Feelings and Abstract Senses (14.10.2025)

- Motivation (04.11.2025)

- The Social Knowledge Base (11.11.2025)

- Potential (18.11.2025)

- The Subliminal Way We Go Through Life (26.11.2025)

- Taking Responsibility (02.12.2025)

- Fishing for Complements (22.12.2025)

- Peter and Fermi (22.12.2025)

🔗 R&R Navigation

Back to Topics │ Bias as a concept │ CheatSheetHub │ Start: Relativity & Reaction

Leave a comment