Back to Topics │ ⇐ Back │ Start: Relativity & Reaction│ Next ⇒

Nerd Cheat Sheets: – Security in Numbers, The Seven Deadly Sins

Our automatic systems—heartbeat, breathing, reflexes—run without conscious direction.

Part of the brain’s role is to monitor our sensory environment and interpret both physical signals (sound, light, touch) and abstract ones such as fairness, trust, or time. When a situation demands attention, the brain releases chemical messengers—adrenaline, dopamine, norepinephrine—not only to prepare the body for action but to sharpen focus and align emotion, thought, and movement.

These emotional surges are signals — a fast prediction of consequences that ask for action: grief helps us mourn, anger prepares us to fight, love bonds us to others.

Take the stegosaurus as an illustration: a slow herbivore living under constant threat, reacting instinctively to danger. Like modern reptiles, it likely operated through primitive emotional analogues—fear, hunger, and territorial drive.

Motivation is the set of emotions and urges that drive behaviour. As we interpret what we experience, activity between the cortex and the limbic system forms opinions and expectations. Each influences the other—thought shapes feeling, and feeling shapes thought.

The limbic system then releases chemical signals that colour mood and promote specific responses:

- Fear protects.

- Anger mobilises.

- Desire sustains species and innovation.

- Sadness prompts reflection.

- Attachment maintains social bonds.

From past experience and current mood, an emotion arises and pushes toward action.

| Limbic State | Cognitive Expression (what we feel consciously) | Example Thought |

| Fear / anxiety | Uncertainty, caution | “I’m not sure I should do this.” |

| Reward anticipation | Confidence, motivation | “This feels right—let’s go for it.” |

| Loss / sadness | Resignation, reflection | “What’s the point right now?” |

| Curiosity / arousal | Fascination, engagement | “I wonder how this works.” |

| Conflict between drives | Ambivalence | “I want to, but something feels off.” |

(Interpretation occurs mainly in the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex, which evaluate limbic output in context.)

Anyone who has been in love—verliebt in German—knows the power of emotion to override rational thought. Being in love is neurochemically intense: dopamine and norepinephrine surge while analytical processing quiets. In art and myth, love often borders on madness for good reason.

In The Matrix Reloaded, the Merovingian serves a cake engineered to trigger a lust response, then remarks on how predictably the events unfold—like dominoes falling. To him, emotion proves choice an illusion.In reality:

Predictable emotion ≠ absence of choice

It only means we must catch the emotion before it dictates the action

Having experienced clinical depression, I found the feeling equally consuming—difficult to resist, almost gravitational. At its depth, simply continuing forward was an achievement. Engaging in an activity and finding flow offered temporary relief. Depression reflects a complex imbalance of brain chemistry, stress response, and cognition, and demonstrates how powerful neurochemistry truly is.

This introduction grounds a simple fact: brain chemistry heavily shapes how we react.

That architecture evolved over roughly two to three million years and served our prehistoric ancestors well. The cognitive limitations that bias our decisions today were not handicaps then—they were efficient survival tools.

Evolution of Social Behaviour

The Nerd Cheat Sheet: Security in Numbers explores the evolutionary forces that encouraged cooperation in social groups, from the animal kingdom to early human societies and, later, the agricultural revolution.

When we think of group behaviour, we picture flocks of birds, shoals of fish, or migrating herds of caribou. Their survival advantage rests on two principles:

- A predator struggles to single out one individual among many.

- Each member’s chance of becoming today’s victim decreases—unless it lags behind or acts unpredictably.

This coordination is instinctive, triggered by environmental cues such as predation or migration. At its root, herd behaviour deceives the predator’s perception—an early example of deception as survival strategy.

True social cooperation, however, requires individuals to act deliberately for the benefit of the group, sometimes at personal cost. Here, social drivers diverge between herbivores and carnivores.

Wolves recognise individuals, form hierarchies, and adjust tactics based on experience—evidence of intentional cooperation rather than reflex synchrony. A pack is usually a family: an alpha pair and offspring from several years. Cooperation extends beyond hunting to guarding, pup-rearing, and territory defence. These roles demand planning, communication, and emotional restraint.

Gorillas and other great apes maintain order through dominance. Strength, tolerance, and occasional deception keep peace. Small doses of dark-triad traits—narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy—can test social boundaries and even enhance short-term success, but chronic dominance risks collapse.

Humans evolved along a mixed path. Early hominins were omnivorous; with Homo erectus came cooperative hunting, and the later agricultural revolution transformed predation into food management. Our lineage carries the social instincts of both predator and prey: carnivorous coordination and herbivorous caution.

Among apes and chimpanzees, deception within the group is common and tolerated to a point—a sign of flexible intelligence.

Group Dynamics

Anthropological evidence suggests that stable hunter-gatherer communities rarely exceeded about 150 individuals—the limit at which everyone could maintain personal relationships (Dunbar’s Number). Within such groups, perhaps 10–20 held real influence: elders, hunters, or mediators. Too few leaders and structure collapses; too many and rivalry fragments unity.

Effective cooperation among leaders demands:

- Shared benefit from joint participation.

- Robust yet adaptable hierarchy.

- Operational flexibility for lower-ranking leaders.

- Mutual understanding of each role’s impact on the whole.

In early societies, such cooperation required emotional restraint, empathy, foresight, and an emerging moral intelligence.

As Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek reminded us through Spock, pure logic mistrusts emotion because emotion feels unpredictable. Yet rejecting feeling also dulls life’s richness. Emotion is not the enemy; unexamined reaction is.

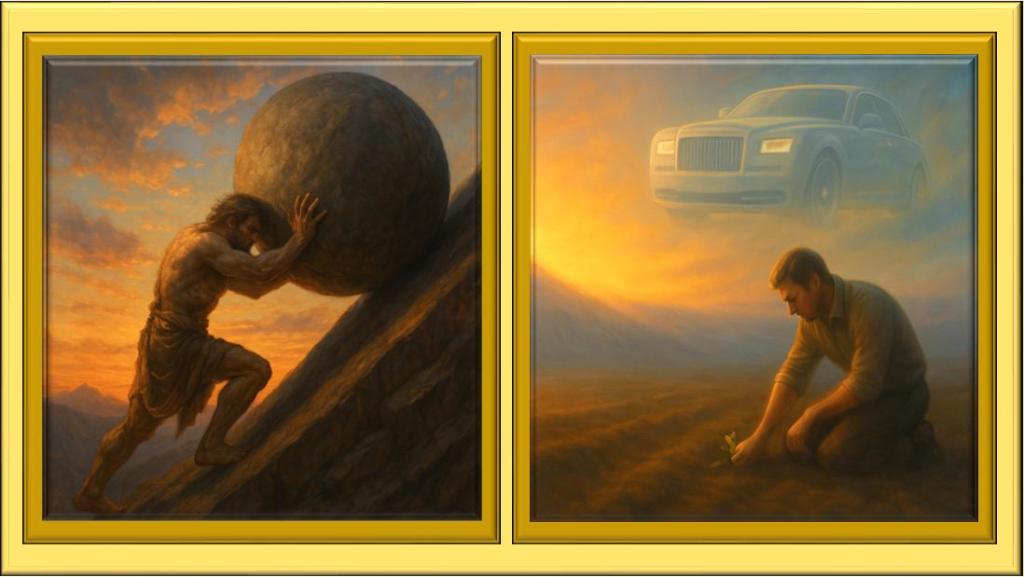

When a challenge arises, our emotions push for rapid, automatic responses. These impulses originate in the limbic system—an older neural circuit tuned for survival, not long-term strategy.

The Nerd Cheat Sheet: The Seven Deadly Sins – Internal vs External explores what earlier ages labelled the darker side of the human ego. These impulses are not sins; they are signals. The challenge—and the opportunity—is what follows recognition.

Self-centred urges or the impulse to harm emerge when our inner values are threatened. The constant reality of life is that such challenges will arise; mastery lies in responding well.

A useful image comes from every flight-safety demonstration:

“If cabin pressure drops, oxygen masks will fall from the compartments above. Place your mask on first before assisting others.”

It is a reminder of responsibility: stabilise yourself before helping anyone else.

Summary

Regret is the consequence of a poor decision, but regret alone rarely heals. Poor decisions are part of learning. Rash decisions occur when we act before understanding our feelings.

Our gut-level systems are vital for survival, yet they are fast, reactive, and narrow in scope. Emotions surface before reasoning catches up. Fighting them is futile; guiding them is wisdom.

We can feel the twist of envy, the flare of anger, the drag of inertia—and still take the next step mindfully. That is not weakness.

That is mastery.

Footnote

Historically, the concept of the Seven Deadly Sins was used as a moral instrument to control thought and behaviour within hierarchical societies. While overt enforcement has lessened, subtle forms of external regulation remain—and everyone, everywhere, still contends with the same emotional forces.

📖 Series Roadmap

- Forward: A Little Background

- Introduction: Action, Reaction, and the Human Paradox (16.09.2025)

- Looking Back in Time: The Development of the Human Brain (23.09.2025)

- Abstract Senses: Enhancing the way we see the world outside (30.09.2025)

- Bias as a Concept & Climbing the Stairs: Pattern Recognition & Everyday Tasks (07.10.2025)

- Abstract Feelings and Abstract Senses (14.10.2025)

- Motivation (04.11.2025)

- The Social Knowledge Base (11.11.2025)

- Potential (18.11.2025)

- The Subliminal Way We Go Through Life (26.11.2025)

- Taking Responsibility (02.12.2025)

- Fishing for Complements (22.12.2025)

- Peter and Fermi (22.12.2025)

🔗 R&R Navigation

Back to Topics │ ⇐ Back │ Start: Relativity & Reaction│ Next ⇒

Nerd Cheat Sheets: – Security in Numbers, The Seven Deadly Sins

Leave a comment