Back to Topics │ Motivation │ CheatSheetHub │ Start: Relativity & Reaction

End Notes: The Seven Deadly Sins – Internal vs External

Observations

Observation: Large Gatherings of the Same Species

Birds flock, fish swim in shoals, and caribou migrate as massive herds to improve their survival.

This has two main aspects:

• Targeting one individual in a large number is difficult for a predator.

• The probability of becoming today’s victim is reduced—unless one falls behind, stands out, or acts unpredictably.

To belong to such a group requires no fixed leader—only simple local rules followed by each individual:

• Keep a certain distance from neighbors.

• Align with their direction.

• Move toward the group center if separated.

Each individual reacts only to its nearest neighbors (usually within a few body lengths).

Information spreads through the group as a wave, like ripples on water, allowing rapid, synchronized motion without a single point of command.

This collective behavior maximizes cohesion and survival, minimizing the risk that one confused leader could endanger the whole.

(Supported by Ref. 1–3)

Observation: Social Behaviour in Birds

Both mammals and birds faced similar survival challenges: managing group behavior, raising offspring, coordinating under threat, and optimizing long-term survival.

However, advanced social interaction occurs only in a limited number of intelligent bird species:

• Corvids (crows, ravens, magpies) and parrots form long-term social groups where individuals recognize each other, remember interactions, and sometimes cooperate intentionally (e.g., mobbing predators, food sharing, or problem-solving).

• In these cases, cooperation can involve theory of mind—a sense of what another bird knows or intends.

• Co-operative breeders (such as some jays or weaverbirds) deliberately assist relatives in raising offspring—an evolved strategy based on kin selection rather than instinctive flocking alone.

Because of evolutionary branching, birds developed a different neural solution from mammals:

• Mammals: cortex-based—layered, chemically modulated, slow but rich in nuance.

• Birds: functionally analogous to the mammalian cortex—the pallium, compact, hyper-efficient, structurally different but convergent in function (notably in corvids and parrots).

(Supported by Ref. 4–6)

Observation: The Social Interaction of Wolves

Wolves are powerful predators that hunt cooperatively to overcome larger prey.

They operate in small groups that are socially and consciously cooperative but not sexually motivated in day-to-day function.

Structure:

A pack is typically a family unit—an alpha (breeding) pair and offspring from multiple years.

Only the breeding pair usually reproduces, so others behave “asexually”: they cooperate for survival and shared genetics.

Conscious cooperation:

Wolves coordinate complex activities—hunting, guarding, pup-rearing, defending territory.

These actions require planning, communication, and role awareness.

Social awareness:

They recognize individuals, form hierarchies, and adjust tactics based on experience—evidence of intentional cooperation rather than instinctive synchrony.

Cognitive layer:

Unlike herd animals, wolves display goal-directed teamwork—anticipating others’ actions, dividing labor, and learning from past hunts.

Social conflict can be detrimental if chronic or destabilizing.

Packs rely on trust and synchrony; unresolved conflict undermines both.

Modern ethology recognizes the “alpha” not as a tyrant but as the breeding or parent pair whose authority derives from maturity and experience.

Older wolves often relinquish leadership as strength declines.

(Supported by Ref. 7–8)

Observation: The Social Interaction of Gorillas

Humans and apes descend from mostly plant-eating ancestors.

For herbivores, food is abundant yet scattered; cooperation focuses on territory, safety, and reproduction rather than coordinated predation.

In many herbivorous mammals—deer, antelope, gorillas, baboons—males compete for control over females rather than for shared prey.

Success depends on:

• physical strength,

• social intimidation,

• and the ability to protect and monopolize females and offspring.

The dominant male’s genetic success relies on protecting his females and offspring; his control of mating is maintained through strength and tolerance, though females retain some choice.

Unlike the hunter who must cooperate to bring down large prey, the gorilla secures his lineage through possession and control of resources.

(Supported by Ref. 9–11)

Observation: The Social Interaction of Humans

As stated before, humans are descendants of mostly plant-eating ancestors.

Our deepest background is herbivorous—searching for and gathering food while remaining alert to predators.

Early priorities were territory, safety, and reproduction.

Between 1.8 and 2.0 million years ago, the human evolutionary path reached the juncture of Homo erectus, shown in the evolutionary table below:

| Species | Time frame | Meat use | Notes |

| Australopithecus | 4–2 Mya | Rare/scavenged | Mostly vegetarian |

| Homo habilis | 2.4–1.6 Mya | Scavenging | Early stone tools |

| Homo erectus | 1.8 Mya–300 kya | Regular hunting | Fire, cooking, large brain |

| Homo sapiens | 300 kya–present | Full omnivore | Cultural control of diet |

Homo erectus was not yet a top-tier predator but displayed the behavioral shift toward cooperative hunting—the wolf’s logic applied to a primate.

(Supported by Ref. 12–15)

Observation: The Agricultural Revolution

About 10–12 thousand years ago, Homo sapiens behavior evolved toward cultivation of crops and domestication of animals—the Agricultural Revolution.

• When humans settled and began farming, ownership replaced cooperation as the primary survival driver.

• Land, surplus, and inheritance created a new kind of social selection: dominance without shared risk.

• The “warrior” became the “landlord”—still powerful but detached from the cooperative logic that once earned leadership.

This marks the divergence between the evolved cooperative brain and the socially constructed ego.

The risks of starvation and injury for the farmer were significantly reduced compared with those of the hunter.

Working members of the tribe became steadily more productive, and food supply less unreliable.

Yet fixed territory required defense—from predators such as foxes and wolves, and from human rivals tempted by neatly organized fields and livestock.

(Supported by Ref. 16–18)

Consequences

Consequence: Large Gatherings of the Same Species

Herds, flocks, and shoals rarely form around mating pairs or family units.

Males, females, and juveniles move together; leadership is transient and situational.

Emergent order replaces hierarchy—the group behaves intelligently without any individual understanding the whole.

The group’s advantage lies in the speed and reliability of local reactions—a living network that “thinks without thinking.”

Such organization is instinctive and largely asexual, triggered by environmental cues like predation pressure or migration.

(Supported by Ref. 1–3)

Consequence: Herd Behavior as Collective Deception

At its root, herd behavior is deception—not of individuals within the group, but of the predator’s perception.

• A moving herd confuses outline, distance, and direction.

• Synchronous movement or coloring distorts targeting.

• Birds, fish, and ungulates create a visual illusion of unity—statistical camouflage through numbers.

Thus, herd behavior is a macro-scale deception strategy born from prey psychology.

Deception as the first resort of the hunted:

Across evolution, the default defense of prey is deception—visual, behavioral, or chemical:

• Camouflage (stick insects, leaf moths)

• Mimicry (viceroy vs. monarch butterflies)

• Startle patterns (“eye-spots” on wings or fins)

These exploit the predator’s pattern-recognition system.

Deception is the first defense before speed, fight, or cooperation.

Predators deceive rarely—and differently.

Because they initiate attacks, they rely on stealth, not disguise.

A few species—angler fish, trapdoor spiders, snapping turtles—use lures or ambush tactics, but these are exceptions.

(Supported by Ref. 3)

Consequence: Social Behavior in Birds

Bird intelligence is primarily cognitive and perceptual rather than affective.

Empathy is limited but not absent—mediated by mexoticin, an analogue of oxytocin.

Cooperation is situational, not identity-based; birds act through perceptual precision rather than lived emotional relationship.

This represents convergent evolution of intelligence—evidence that “mind” is not a fluke of mammalian biology but a broader adaptive principle.

(Supported by Ref. 4–6)

Consequence: The Social Interaction of Wolves

Wolves blend instinctive cohesion with deliberate cooperation.

Their operational behavior is strategic, relational, and intelligent.

| Group type | Motivation | Coordination mechanism | Conscious intent? | Example |

| Flocks / Herds | Survival | Emergent alignment | No | Starlings, caribou |

| Packs / Troops | Family survival | Planned cooperation | Yes | Wolves, lions, chimpanzees |

| Human societies | Collective / abstract goals | Communication, institutions | Highly variable | Humans |

To preserve cohesion, wolves evolved conflict-resolution mechanisms:

- Hierarchy – prevents constant fighting; roles are clear.

- Ritualized submission – body language defuses aggression without injury.

- Cooperative dependence – shared success pressures reconciliation.

- Expulsion – a release valve for irreconcilable conflict.

An older breeding wolf often yields leadership instinctively, maintaining pack stability.

In evolutionary terms, ego is a liability: it introduces hesitation and division.

The wolf serves the function of power until that function is better served by another.

(Supported by Ref. 7–8)

Consequence: The Social Interaction of Gorillas

For gorillas, the simplest way to resolve conflict is brute force.

Dominance maintains order; deception and tolerance are social tools.

Small doses of dark-triad traits—narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy—can test social tolerance and enhance short-term survival, but chronic dominance risks collapse.

When cooperation fails, brute hierarchy prevails—a pattern echoed in many human systems.

(Supported by Ref. 9–11, 19–20)

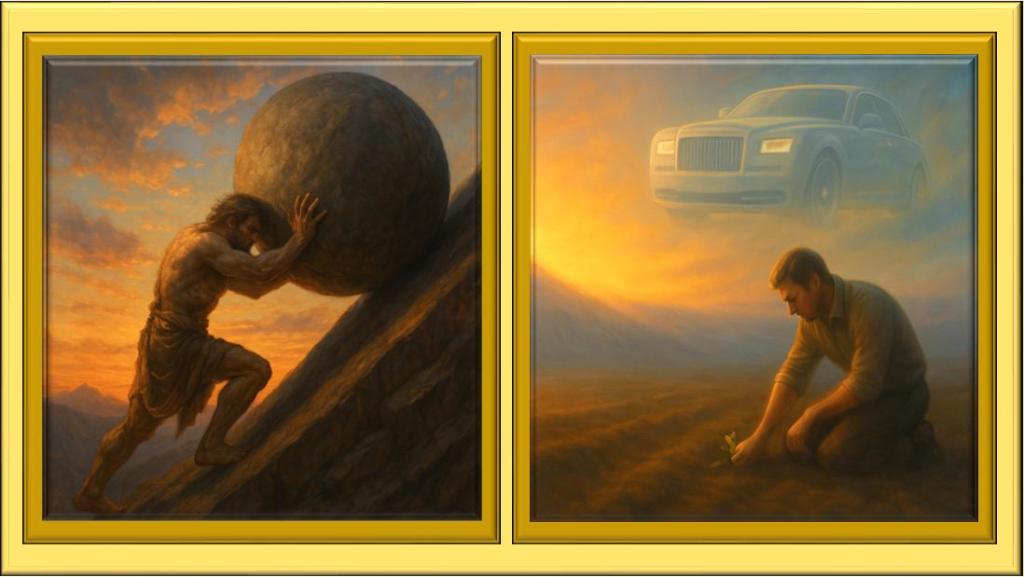

Consequence: The Social Interaction of Humans

The evolutionary path of Homo sapiens begins in the vegetarian branch of mammals.

The move to an omnivorous diet was significant—it required a behavioral change from hunted to hunter.

Homo erectus represents the turning point: cooperative hunting and shared risk.

The cooperative drives that shaped wolves began to shape early humans as well.

The Agricultural Revolution:

The harsh reality of agriculture is that it turned the prey of primitive man into crops.

• Dominance without shared risk.

• The “warrior” became the “landlord”—still powerful but detached from the cooperative logic that once earned leadership.

This marks the divergence between the evolved cooperative brain and the socially constructed ego.

This mode of living became a reversion to the lifestyle of the gorilla: resource control, defense, and hierarchy.

Nature makes life harsh for all who live under its rule, and the greedy landowner has his troubles to bear.

A fox in the henhouse kills more than it can eat; instinct doesn’t recognize “enough.”

When humans gathered their food and animals behind fences, they created both temptation and opportunity.

The fox became the thief at the gate, and the rescuer-for-hire became the super-human—the high-born protector of the homestead.

The community began to pay for safety—first in grain, later in coin.

What began as cooperation evolved into tribute, and tribute hardened into tax.

Seeing that coin had not yet been invented, the farmer turned to the knight in shining armor and said,

“Thank you for your service, good knight. Would you care for some apples? Mine have the taste of enlightenment.”

And in that moment, it was left to the gods to decide who should eat the best apples.

(Supported by Ref. 12–18)

Action

From the standpoint of the individual, evolution has left a few cuckoo eggs in the nest.

They hatched from ancient survival needs—particularly within the hunter-or-hunted dynamic.

These traits are not the work of the devil; they were once essential tools for staying alive.

In the vast societies we inhabit today, however, those same traits have become a problem.

The dark triad—narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy—takes more than its fair share of resources.

Like the fox, such behavior does not recognize when “enough” has been reached.

To counter this, our observations must be grounded—anchored in fact rather than impulse—so that our contributions remain impartial.

And our arguments must be persuasive, not manipulative, for only then can our actions stay stable, reasonable, and genuinely effective.

📖 Series Roadmap

- Forward: A Little Background

- Introduction: Action, Reaction, and the Human Paradox (16.09.2025)

- Looking Back in Time: The Development of the Human Brain (23.09.2025)

- Abstract Senses: Enhancing the way we see the world outside (30.09.2025)

- Bias as a Concept & Climbing the Stairs: Pattern Recognition & Everyday Tasks (07.10.2025)

- Abstract Feelings and Abstract Senses (14.10.2025)

- Motivation (04.11.2025)

- The Social Knowledge Base (11.11.2025)

- Potential (18.11.2025)

- The Subliminal Way We Go Through Life (26.11.2025)

- Taking Responsibility (02.12.2025)

- Fishing for Complements (22.12.2025)

- Peter and Fermi (22.12.2025)

🔗 R&R Navigation

Back to Topics │ Motivation │ CheatSheetHub │ Start: Relativity & Reaction

End Notes: The Seven Deadly Sins – Internal vs External

Leave a comment