Back to Topics │ ⇐ Back │ Start: Relativity & Reaction│ Next ⇒

Nerd Cheat Sheet: – The Fabric of Society

What is Science?

We go through life guided by countless impressions, shortcuts, and assumptions—we rarely notice them, yet they shape everything. So, just as we did in the section on potential, it helps to begin by clarifying a few foundations. In this section, science becomes our lens—not the laboratory version, but the broader cultural idea of science as a search for truth.

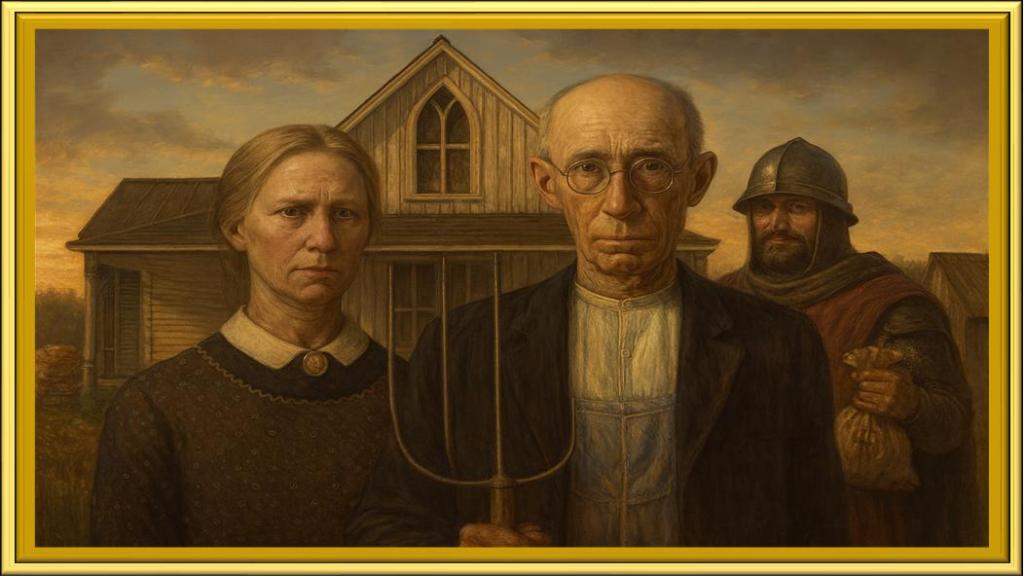

Pop culture captures this surprisingly well. Not as equations or microscopes, but as something deeper:

- Star Trek reminds us:

“The first duty of every Starfleet officer is to the truth—whether it’s scientific, historical, or personal.” - Linus Pauling, a two-time Nobel Prize winner, puts it plainly:

“Science is the search for truth … the effort to understand the world.” - Sheldon Cooper jokes on The Big Bang Theory:

“I don’t need sleep, I need answers… I must find where, in this swamp of formulas, squatteth the toad of truth.” - And another line from the show, attributed in-universe to Einstein (though not historically his), declares:

“The pursuit of science calls us to ignore the rules set by man.”

It echoes Einstein’s real sentiment that the universe does not obey our expectations.

These examples—drawn mostly from American media and shared globally—reflect the Social Knowledge Base (SKB) we all absorb from what we watch, read, and laugh at. Humour is especially powerful here: when someone says “I get it!” to a joke, they are not responding to the punchline but recognising a shared underlying model of the world.

But this search for truth reaches far beyond popular culture. The word science comes from the Latin scientia, meaning “knowledge,” “understanding,” or simply “to know,” which itself comes from scire: “to discern,” “to understand.” Greek and Roman societies, among many others, built cultures around gathering and preserving knowledge. Their languages—Greek and Latin—are now considered Classical Languages. No longer spoken daily, they remain essential scaffolding for law, philosophy, medicine, and science.

Across time and culture, the idea stays the same: science is connected to truth. To know something feels like uncovering a small piece of how the world really works. But that feeling hides a paradox—if you believe you already know the truth, you stop looking. The search ends. And that’s the dangerous part.

The real wisdom lies not in what you know, but in recognising what you don’t.

As the old lesson goes:

“Knowing what you don’t know is the root of wisdom.”

But even science can be slowed or misdirected when belief outruns evidence.

What Einstein’s Theories Tell You and Me

In the section on potential, we looked at the Michelson–Morley experiment of 1887, which challenged the old idea of an ether—a medium once thought necessary for light to travel through space. Today we understand light as a self-propagating electromagnetic wave, requiring no carrying medium. Einstein’s Special Relativity (1905) did not explicitly reject the ether, but by assuming that the speed of light is constant for all observers, it made the ether unnecessary.

Less well appreciated is that Maxwell’s equations (1860s) already described light as an electromagnetic wave—and the mathematics itself did not require an ether. But the cultural mindset of the period did. The idea that waves must have a medium was deeply embedded in the scientific SKB, so even Maxwell accepted it by default.

From Maxwell’s equations in the 1860s to Einstein’s Special Relativity in 1905, nearly half a century passed—two or three scientific generations. Even after the Michelson–Morley null result, another eighteen years—roughly one full generation—were needed before the ether was finally abandoned. The evidence had been there long before the mindset changed.

We have no “fly on the wall” record of the debates, arm-twisting, and philosophical wrestling needed to shift physics from a universe filled with ether to one without it. But we know the shift was painful.

Einstein’s General Relativity (1915) then revealed the limits of Newton’s picture of gravity. It is often described as “bending light,” but that phrasing exposes the limits of our intuitions. In everyday life, bending a path requires a force acting on something. Light, however, has no rest mass and nothing for a force to push against. Einstein resolved this by showing that gravity is not a force at all—it is the shape of spacetime. Light always travels straight, but in curved space that straight line can look bent to us.

The confusion we feel when imagining this is not a flaw in us—it is a sign that our mental models were shaped for a Newtonian world, not an Einsteinian one. Our abstractions reach their limits.

Meanwhile, in the background, Max Planck (1900) proposed a radical idea to fix a problem with blackbody radiation:

- energy comes in discrete packets, quanta

- introduced as a mathematical adjustment, not a philosophical claim

- later interpreted as a profound truth about nature

Einstein himself, in 1905, extended this idea by proposing the photon.

This marks the start of the quantum revolution.

The Battle for the Soul of Physics

Had Stephen Fry been writing this, he might have invoked Olympian gods and ancient metaphors. Instead, we face real titans—Einstein, Planck, Bohr, Heisenberg, Schrödinger—locked in a struggle over the nature of reality.

Einstein felt betrayed by Bohr, Heisenberg, and the Copenhagen school. He believed the universe must be:

- orderly

- deterministic

- smooth

- elegant

- logical

- and describable in clear physical terms

Quantum mechanics arrived and said:

- sometimes events are random

- particles do not have definite positions until measured

- reality contains probability

- the universe is not fully knowable

To Einstein, this felt like treason. He saw himself as defending sanity against chaos. He dismissed quantum mechanics as “incomplete,” and famously used the word “abominable.”

But from the Copenhagen perspective, Einstein was the traitor.

Bohr and Heisenberg believed he was clinging to the past, unwilling to accept new evidence, trapped by philosophical baggage. Heisenberg even said:

“Einstein, stop telling God what to do.”

This was not polite disagreement. It was a scientific civil war.

The Solvay Conferences of 1927 and 1930 were its battleground: Einstein vs. Bohr, determinism vs. probability, realism vs. mysticism. They argued day and night—sometimes until 3 AM. Contemporary accounts describe an atmosphere that was tense, combative, personal, and dramatic. Einstein produced thought experiments to expose flaws; Bohr dismantled them one by one.

Journalists called it “the battle for the soul of physics.”

Both sides accused the other of betrayal.

Einstein believed:

- Bohr betrayed realism

- Heisenberg betrayed causality

- quantum mechanics betrayed physics itself

The quantum camp believed:

- Einstein was slowing progress

- he refused to update outdated assumptions

- he was betraying the revolution he helped start

We are not so different from Einstein in those moments. When new information threatens our internal model of the world, resistance feels rational.

Where Theory Meets Technology

To see what these theories actually gave us, here is a summary:

| Theory | Core Idea | Technologies Enabled |

| Special Relativity (1905) | Speed of light is constant; time and space adjust to preserve it. | GPS timing, particle accelerators, synchrotrons, nuclear energy calculations |

| General Relativity (1915) | Gravity is curvature of spacetime. | GPS precision, gravitational wave detection (LIGO), black hole imaging, deep-space navigation |

| Quantum Mechanics (1900–1927) | Energy comes in quanta; particles behave as waves; probability rules. | Semiconductors, transistors, lasers, MRI, LEDs, solar panels, atomic clocks, tunnelling microscopes, quantum computing, quantum encryption |

Relativity explains the large-scale architecture of the universe, while quantum mechanics governs the tiny scales of atoms and electrons. But in everyday life, quantum mechanics dominates. Nearly every modern technology—from phones to computers to medical imaging—rests on quantum principles.

The irony is that both theories describe worlds we cannot see: relativity reveals the very large; quantum mechanics, the very small. The visible human scale is the thin surface between them.

We evolved in Newton’s world, not Einstein’s or Bohr’s. Newtonian physics still works in the middle ground where human life plays out, so our intuition remains Newtonian even though the universe is not

The Social Behaviour of Scientists

“Science is the pursuit of truth” is a noble mission statement. It captures the best hopes of the scientific community: curiosity, honesty, and a willingness to follow evidence wherever it leads. But when the phrase is spoken as an identity—we are the ones who pursue truth—it becomes something else entirely. It slips into confidence, then certainty, and finally into a quiet belief that scientists are somehow exempt from the normal limits of human behaviour.

They aren’t.

The story of Einstein’s relativity and the rise of quantum mechanics makes this clear. The drama between them was not only about the nature of light, gravity, or probability. It was also about the social behaviour of the scientific community: rivalry, status, loyalty, fear of being wrong, fear of being forgotten, and the ever-present pressure to defend one’s place in the intellectual hierarchy.

In other words, the “search for truth” did not elevate scientists above normal human behaviour. Their conduct converged with that of every other group navigating the Social Knowledge Base (SKB). That is why the framework described in the Nerd Cheat Sheet: The Fabric of Society applies just as well here as anywhere else:

- Hierarchy: Who leads and who follows.

- Possession: Who controls ideas, influence, and research territory.

- Security: How individuals are protected or threatened.

- Ritual: The customs and etiquette that maintain order.

Understanding the origins of this framework—and the consequences it produces—helps explain why scientific communities behave the way they do. The structure of society appears everywhere, but each domain implements it differently, leading to different outcomes.

Many modern societies allow a high degree of individual liberty while maintaining structure. Realising that the distribution of wealth—and the control of wealth-generating property—lies at the core of all hierarchies explains why conflicts arise, and also hints at how they might be resolved.

But the key point is this:

Scientists do not stand outside the system. They live inside the same SKB as the rest of us, and their O–C–A process is shaped by it just as ours is.

The Debate and Scientific Information

Even in scientific discovery, Observation rarely leads directly to Action — it must first pass through the beliefs and social structures that shape Consequence assessment.

What we have seen here is no different from political debate or any other human conflict. The Solvay Conferences were closer to a chess championship than a Super Bowl, but the underlying dynamics—tribes, identity, rivalry—were the same.

Scientists are human beings. Their motivations include emotion, reputation, hierarchy, etiquette, and the unwritten rules of their community. These forces shape their behaviour just as they shape every other part of the Social Knowledge Base.

Science is a relationship between people and the state of knowledge today. Understanding evolves. Tomorrow’s truth may clash with today’s certainty.

So whenever someone says, “the science is in,” they should not be handed a blank cheque. Science is powerful—but it is never finished.

My frustration did not come from the science. It came from the way the Social Knowledge Base — the shared mental model of society — was being compressed, simplified, and weaponised. I realised that “the science is in” was never the spirit of science. Science evolves. Models improve. Understanding deepens. Evidence guides us, but it never closes the door.

That moment was the beginning of this whole endeavour. I wanted to understand how communities form beliefs, why they defend them so fiercely, and how each of us can navigate a world where knowledge is both powerful and fragile.

📖 Series Roadmap

- Forward: A Little Background

- Introduction: Action, Reaction, and the Human Paradox (16.09.2025)

- Looking Back in Time: The Development of the Human Brain (23.09.2025)

- Abstract Senses: Enhancing the way we see the world outside (30.09.2025)

- Bias as a Concept & Climbing the Stairs: Pattern Recognition & Everyday Tasks (07.10.2025)

- Abstract Feelings and Abstract Senses (14.10.2025)

- Motivation (04.11.2025)

- The Social Knowledge Base (11.11.2025)

- Potential (18.11.2025)

- The Subliminal Way We Go Through Life (26.11.2025)

- Taking Responsibility (02.12.2025)

- Fishing for Complements (22.12.2025)

- Peter and Fermi (22.12.2025)

🔗 R&R Navigation

Back to Topics │ ⇐ Back │ Start: Relativity & Reaction│ Next ⇒

Nerd Cheat Sheet: – The Fabric of Society

Leave a comment